Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, and frequently, other materials too. This alloy remains the material of choice for most collectors and forms the bulk of Swiss exports. We will defer the usual examination of steel in general, fascinating though it is, and move straight ahead to definitions and the use of the material in watchmaking. Amongst the many alloys of steel-primarily distinguished by how many and what kinds of metals are in the mix-most of you, dear readers, will be familiar with 316L and 904L steel.

Here is what makes up 904L stainless steel, assembled from various sources and first published by us in 2021:

- Nickel, 23-28%

- Chromium, 19-23%

- Carbon, 0.02% maximum

- Copper, 1-2%

- Molybdenum, 4-5%

- Manganese, 2% maximum

- Silicon, 1.0% maximum

- Iron (balance)

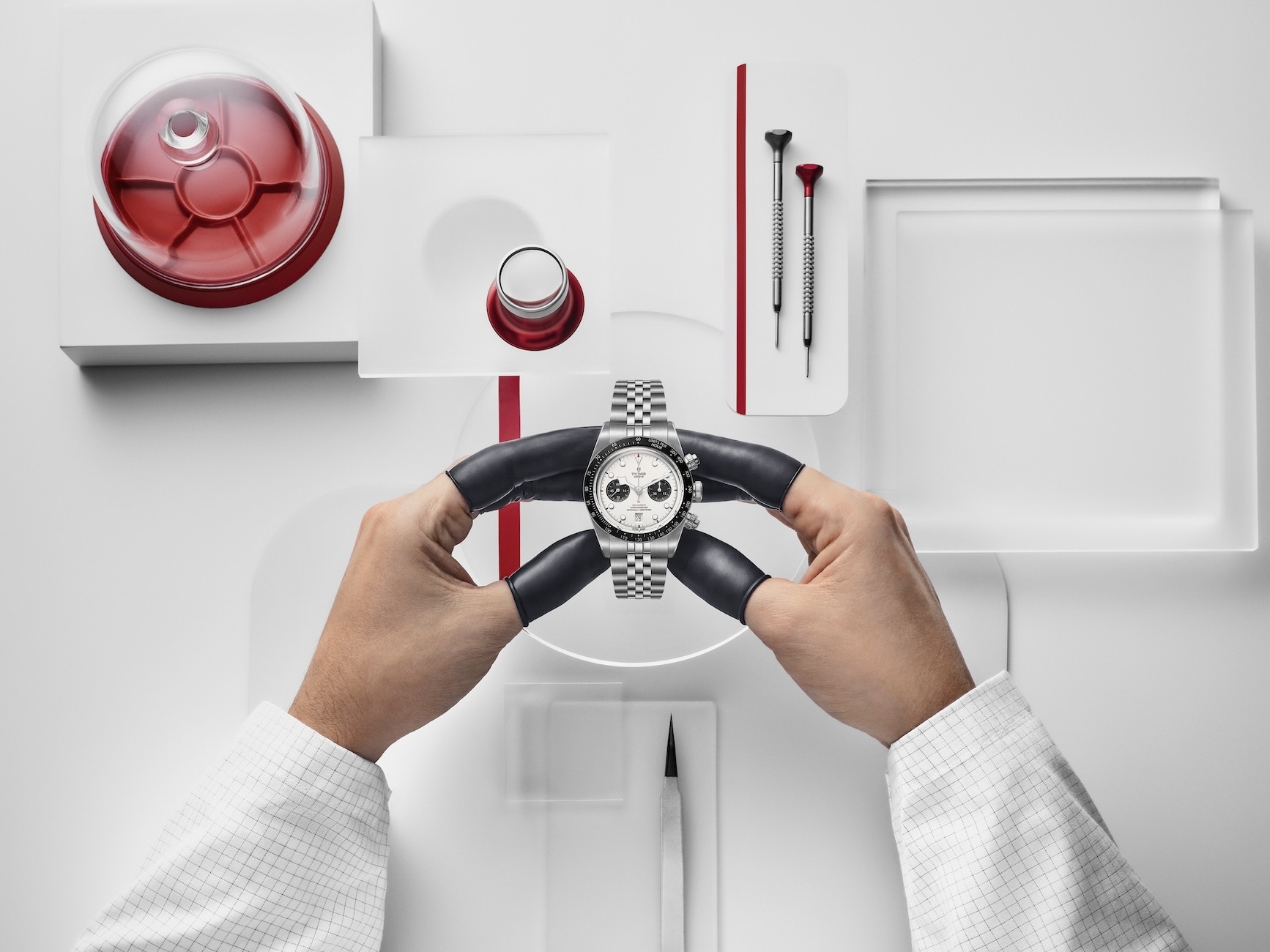

Colloquially, we think of these as stainless steel and this works just fine; some might recognise 904L as OysterSteel, which is one of watchmaking’s earliest efforts to impose a measure of branding on materials. Generalist sources will note that steel was probably used first in the 1910s and then picked up in popularity with the Great Depression. The hardness of the steel (compared with silver and gold) made some kinds of casemaking and finishing techniques impractical, especially the Art Deco styles popular in the 1920s and 30s. Of course, this gave watches different features depending on the materials used.

Steel cases made robust tool watches possible, the usefulness of which was demonstrated by early aviators such as Charles Lindbergh and Santos Dumont, most famously (and fabulously). It is not precisely recorded what sorts of watches were used by artillery officers in WW1, but this is where steel could be expected to shine, no pun intended. In reality, whatever watches could be pressed into service probably were. By WW2, things had gotten more orderly and militaries everywhere had recognised the need for good tools and field watches.

While water-resistance is not directly related to material choice here, the most famous of such cases, the Rolex Oyster, was in steel. With the end of the great wars and the end of rationing, more maximalist consumer habits did not see steel fall by the wayside and the growth of the watch business in this part of the 20th century saw more and more steel models.

We refer here to the Rolex GMT-Master and Daytona watches, but also to the Omega Speedmaster and the Heuer Carrera. All the iconic dive watches also emerged in this time frame, including the Submariner and Fifty Fathoms. Coincidentally and obviously, the rise of the luxury steel sports watch also happened in the 20th century.

As with many observers of the trade, from EuropaStar to WatchTime and WatchAround, and CEOs ranging from Julien Tornare and Guido Terreni to Thierry Stern, we concur that the sweeping tide of casualisation is primarily responsible. As a material, steel happens to benefit from the same cultural changes evident in the normalisation of jeans in professional settings, especially when the dress code is “business casual.” This would hThe Enduring Role of Steel in Watchmakingave been unthinkable 50 years ago.

This story was first seen as part of the WOW #79 Summer 2025 Issue

For more on the latest in luxury watch reads, click here.