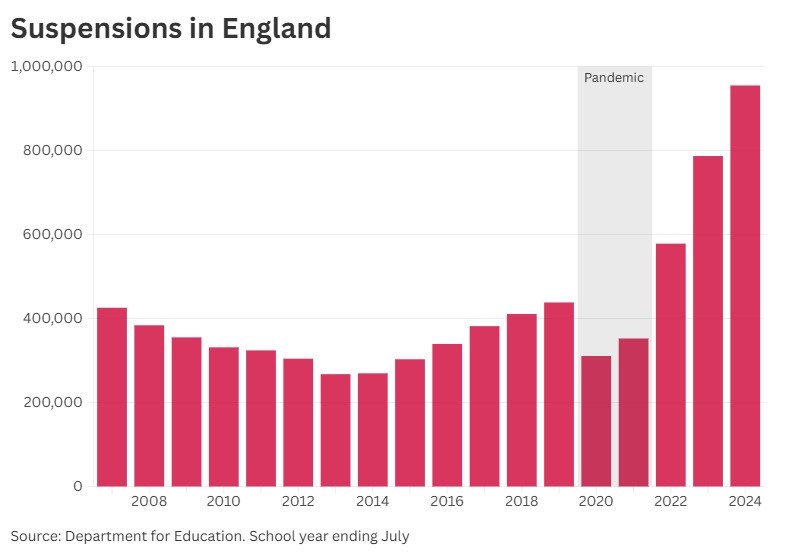

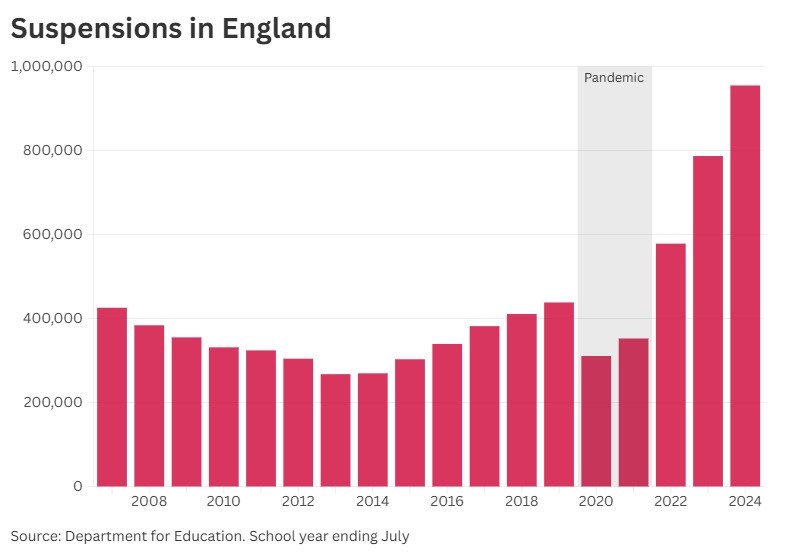

Children are increasingly being removed from English classrooms, with official figures released today showing suspensions trebling in a decade.

While the number of suspensions had been rising steadily since 2013, this has accelerated since the pandemic, reaching 955,000 in the 2023/24 school year.

The Department for Education figures show most suspensions were at secondary level.

But suspensions at primary age were rising fastest, with 104,000 suspensions in the most recent year, up 24 percent on the year before.

Permanent exclusions have also risen steeply, up by 16 percent in a year. There were 10,900 exclusions across England in 2023/24, with 70 children aged four or under among those removed from their schools.

Why are more children being suspended or excluded from school?

The new figures show the most common reasons for suspensions in England were “persistent disruptive behaviour”, followed by verbal abuse or threatening behaviour against an adult and physical assault against a pupil.

FactCheck has previously revealed a rise in attacks on teachers reported by schools across Great Britain.

But there are also concerns about some pupils not getting the extra support they need.

Children with special educational needs (SEN) are three times more likely to be suspended than their classmates, the figures show.

And children from deprived backgrounds – those eligible for free school meals – are four times more likely to be suspended than their classmates.

A total of 341,000 children across England were suspended at least once in 2023/24, the figures show, with many facing multiple suspensions. More than 100,000 pupils missed more than a week of school as a result.

Charities have called on the government to do more to support the most vulnerable pupils.

Sophie Schmal, director of early intervention charity Chance UK, told FactCheck: “When you have children as young as five and six years old being permanently excluded from school then clearly something is going very wrong.

“Every day, we see children and families being let down by a system that is failing to support them early enough.”

Mission 44, the education charity founded by Formula One driver Sir Lewis Hamilton, said disadvantaged children were being sent home rather than supported.

Its chief executive, Jason Arthur, said: “This crisis demands urgent, targeted investment and bold political will.”

Early education minister Stephen Morgan said the government’s “Plan for Change” was “tackling the root causes of poor behaviour, including by providing access to mental health support in every school”.

He said new Attendance and Behaviour Hubs will directly support the 500 schools that need the most help and the Government was “continuing to listen to parents as we reform the SEND system”.

How does England compare with Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland?

Wales and Northern Ireland have also seen suspensions rise over the past decade, although rates remain lower than in England.

There’s a different picture emerging in Scotland, where the Scottish government has a sometimes-controversial policy to use exclusions only as a “last resort”, concerned about the effect they can have on excluded children.

First minister John Swinney MSP told First Minister’s Questions last month that exclusions can have “negative consequences”.

Scotland only publishes exclusion figures every other year and is not expected to release any this year.

But data for the school year 2022/23 show suspensions in Scotland fell by 47 percent – nearly half – in 10 years.

Permanent exclusions that year? Just one.

(Image credit: Shutterstock)